PAIRED TEXTS: OZIAN STUDIES

31 July 2011

20 May 2011

What do animals have to do with it?

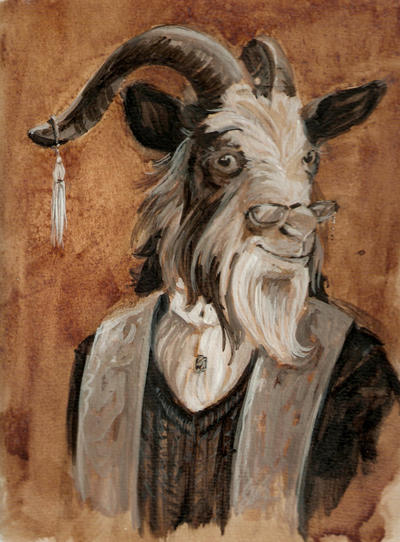

So far in our reading of Wicked we have come across the main social issue in Oz; animal rights. Some of the Animals in Oz are very intelligent like Dr. Dillamond for example; he is a professor at Shiz University yet he is a goat. The head of Shiz however does not appear to like the idea of animals having the same rights so in her Quells that she recites, a lot of the animals get upset because she ends with the line “Animals should be seen and not heard” (pg 84, Wicked) We soon find out that the law has been passed and so for the future generations of Animals are no longer allowed to maintain “human” jobs or ride public transportation. Their rights have been taken away. We do not yet understand why this is happening though. After having already read The Wizard of Oz, which takes place after this law is in order, we do not see any animals in society. There are no Animals in Munchkinland or in the Emerald City. What is the purpose of this? We can see that clearly these animals are capable of withholding jobs and they can be extremely intelligent so why is there now a ban against them?

“I have been making believe”: religion in “The Wonderful Wizard of Oz”

All divine in “The Wonderful Wizard of Oz” was revealed to be plain and deceptive. The godly figure – Wizard comes down to Earth with a confession “I am a humbug” (Baum, 184). A curious deprecation happens to the evil part of the polytheic pantheon. Wickedness of the Witch of the West is wiped by water as if in a ritual of baptism. The only divine part stays in Glinda, but still it is rather goodness than supernatural that upraises her. So what kind of a conclusion does the reader may come to? Knowing that Baum was a theosophist, it could be assumed that he applied this idea to the book as well, since Dorothy’s quest resembles a quest for “truth”.

All divine in “The Wonderful Wizard of Oz” was revealed to be plain and deceptive. The godly figure – Wizard comes down to Earth with a confession “I am a humbug” (Baum, 184). A curious deprecation happens to the evil part of the polytheic pantheon. Wickedness of the Witch of the West is wiped by water as if in a ritual of baptism. The only divine part stays in Glinda, but still it is rather goodness than supernatural that upraises her. So what kind of a conclusion does the reader may come to? Knowing that Baum was a theosophist, it could be assumed that he applied this idea to the book as well, since Dorothy’s quest resembles a quest for “truth”. The details in the book, though, provide examples of self-reliance more than an appeal to God. The only might-be “candidate” for god, the Wizard, simply says: “I have been making believe” (Baum, 184).These words basically summarize the question of religion in the Land of Oz, just like the prejudices of companions about their own incapabilities to use brain, heart and courage. In the whole book, there is not a single mentioning of a word “god”. However, there is a church that is broken – in the china land, which is symbolic of the importance of religion. Literally, Dorothy does not find any damage in destroying a sacred place: I think we were lucky in not doing these people more harm than breaking a cow’s leg and a church” (Baum, 234).

The details in the book, though, provide examples of self-reliance more than an appeal to God. The only might-be “candidate” for god, the Wizard, simply says: “I have been making believe” (Baum, 184).These words basically summarize the question of religion in the Land of Oz, just like the prejudices of companions about their own incapabilities to use brain, heart and courage. In the whole book, there is not a single mentioning of a word “god”. However, there is a church that is broken – in the china land, which is symbolic of the importance of religion. Literally, Dorothy does not find any damage in destroying a sacred place: I think we were lucky in not doing these people more harm than breaking a cow’s leg and a church” (Baum, 234). There is no god as an entity, but perhaps Baum meant that there is enough of godly power in the self – in Dorothy and her companions. Perhaps, it was all about stopping to turn the sights to the sky that keeps silent after the storm. The question of religion in Oz is open – should there be faith or must there be enough to hold on within the self?

Unlike Baum, Gregory Maguire makes a significant accent on religion. The struggle between Pleasure Faith and Unionism poses a moral dilemma of extremes versus modesty. The importance of faith in “Wicked” makes the reader assume that the accent was intended by Maguire to oppose the absence of faith in Baum’s Oz. Thus, “Wicked” promises a clearly depicted faith theme and problem, though it seems like a lot of the questions will still be up to the reader to answer.

There is no god as an entity, but perhaps Baum meant that there is enough of godly power in the self – in Dorothy and her companions. Perhaps, it was all about stopping to turn the sights to the sky that keeps silent after the storm. The question of religion in Oz is open – should there be faith or must there be enough to hold on within the self?

Unlike Baum, Gregory Maguire makes a significant accent on religion. The struggle between Pleasure Faith and Unionism poses a moral dilemma of extremes versus modesty. The importance of faith in “Wicked” makes the reader assume that the accent was intended by Maguire to oppose the absence of faith in Baum’s Oz. Thus, “Wicked” promises a clearly depicted faith theme and problem, though it seems like a lot of the questions will still be up to the reader to answer.

Wicked: Why give background to the Wicked Witch?

In L. Frank Baum’s The Wonderful Wizard of Oz each character has a unique background. Dorothy is small farm girl from Kansas (Baum 12). The Scarecrow talks about how he was made by a farmer and put up to guard the field, but left without a brain (47). The Tin Woodman tells of his lost love for a Munchkin woman and how he was cut to pieces by the Witch and put back together with tin (59). Then there is the Lion who tells of his woes as he supposed to be a fearsome creature yet in reality he is merely a coward (67). Even the Wizard has a back-story, floating into Oz in a weather balloon (187). Strangely Baum fails to incorporate a history for the Wicked Witch, other than other characters' accounts as to what horrible crimes she has done. This is where Gregory Maguire has taken the liberty to fill in the blanks for readers. He gives background to the witch who stands for evil and opposes Baum’s companions in their quest to receive the Wizard’s gifts, regarded as one of the ultimate villains of all time.

In L. Frank Baum’s The Wonderful Wizard of Oz each character has a unique background. Dorothy is small farm girl from Kansas (Baum 12). The Scarecrow talks about how he was made by a farmer and put up to guard the field, but left without a brain (47). The Tin Woodman tells of his lost love for a Munchkin woman and how he was cut to pieces by the Witch and put back together with tin (59). Then there is the Lion who tells of his woes as he supposed to be a fearsome creature yet in reality he is merely a coward (67). Even the Wizard has a back-story, floating into Oz in a weather balloon (187). Strangely Baum fails to incorporate a history for the Wicked Witch, other than other characters' accounts as to what horrible crimes she has done. This is where Gregory Maguire has taken the liberty to fill in the blanks for readers. He gives background to the witch who stands for evil and opposes Baum’s companions in their quest to receive the Wizard’s gifts, regarded as one of the ultimate villains of all time.

Maguire adapts Baum’s characters in order to explore perceptions. When we meet Baum’s companions in The Wonderful Wizard of Oz they seem like an unlikely group of friends who are the ultimate underdogs, getting to Oz with luck and unknowingly good deeds. However, Maguire chose to first introduce them while they are gossiping about the Wicked Witch. The Lion, Tin Woodman and Scarecrow are repeating rumors they have heard about the witch while Dorothy sits complacently and listens (Maguire 1). Their gossip includes the Witch’s sexuality, gender, upbringing and almost anything else they can conjure up (2). This makes the reader feel sorry for the witch who happens to be sitting in a tree listening from above. She is hurt by their words and unlike in Baum’s novel, the witch’s emotions are shown through her responses. Maguire allows there to be a totally different perspective on the Witch. Maguire lets the reader know that there is quite possibly a misunderstanding between the Witch and those who are against her.

Maguire adapts Baum’s characters in order to explore perceptions. When we meet Baum’s companions in The Wonderful Wizard of Oz they seem like an unlikely group of friends who are the ultimate underdogs, getting to Oz with luck and unknowingly good deeds. However, Maguire chose to first introduce them while they are gossiping about the Wicked Witch. The Lion, Tin Woodman and Scarecrow are repeating rumors they have heard about the witch while Dorothy sits complacently and listens (Maguire 1). Their gossip includes the Witch’s sexuality, gender, upbringing and almost anything else they can conjure up (2). This makes the reader feel sorry for the witch who happens to be sitting in a tree listening from above. She is hurt by their words and unlike in Baum’s novel, the witch’s emotions are shown through her responses. Maguire allows there to be a totally different perspective on the Witch. Maguire lets the reader know that there is quite possibly a misunderstanding between the Witch and those who are against her.  As Maguire leads through the Witch’s youth it becomes clear that no one quite understands all that she has been through. Maguire backs her with a dysfunctional home life, as well as providing the fuel for the rumors that will follow her throughout her life because of her green complexion and jagged teeth. But what is it about the Witch that makes her so easy to provide background to? Of course her history is conveniently removed from Baum’s novel, but also she provides the most mystery. Why does she act the way she act? What made her the way she is? Not being far enough in the novel it is hard to tell how exactly these perceptions that Maguire puts forth tie into Baum’s novel, however we can see that it is not simply the perceptions of the Witch that Maguire is exploring. Through the Witch he is exploring the entirety of Oz.

Works Cited

Baum, L. Frank. The Wonderful Wizard of Oz. New York: Dover, 1960.

Maguire, Gregory. Wicked: The Life and Times of the Wicked Witch of the West. New York: ReganBooks, 1995.

As Maguire leads through the Witch’s youth it becomes clear that no one quite understands all that she has been through. Maguire backs her with a dysfunctional home life, as well as providing the fuel for the rumors that will follow her throughout her life because of her green complexion and jagged teeth. But what is it about the Witch that makes her so easy to provide background to? Of course her history is conveniently removed from Baum’s novel, but also she provides the most mystery. Why does she act the way she act? What made her the way she is? Not being far enough in the novel it is hard to tell how exactly these perceptions that Maguire puts forth tie into Baum’s novel, however we can see that it is not simply the perceptions of the Witch that Maguire is exploring. Through the Witch he is exploring the entirety of Oz.

Works Cited

Baum, L. Frank. The Wonderful Wizard of Oz. New York: Dover, 1960.

Maguire, Gregory. Wicked: The Life and Times of the Wicked Witch of the West. New York: ReganBooks, 1995.

Perceptions in Wicked and The Wizard of Oz

Within the Wonderful Wizard of Oz by L. Frank Baum the perceptions and perspective of the narratorand other characters portray the goodness of the four companions. The Wicked Witch of West is already preconceived as wicked because of her actions in the Wizard of Oz; however through Gregory Maguire’s specific use of perspective and narrator point of view, in Wicked, the view of the Wicked Witch as Elphaba and her “good” counterpart Galinda, the "Good Witch", is completely changed.

Within the Wonderful Wizard of Oz by L. Frank Baum the perceptions and perspective of the narratorand other characters portray the goodness of the four companions. The Wicked Witch of West is already preconceived as wicked because of her actions in the Wizard of Oz; however through Gregory Maguire’s specific use of perspective and narrator point of view, in Wicked, the view of the Wicked Witch as Elphaba and her “good” counterpart Galinda, the "Good Witch", is completely changed.

Works CIted

“Dorothy Killing Witch” Image. http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/bc/Wicked_Witch2.jpg/250px-Wicked_Witch2.jpg.

“Elphaba from Wicked” Image. https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEh5QL6ugmpaxRtNw8sHW0_U1xiPdIuTNIHWrWqaHuAzx5cSIb5zkZX9dtASP_nWtlOdR6gMAVZJR61NZ94JQU1ldWVGU9WXptsvl5C_kb8eIywS92LevG9MJ-g85Gjm-wYcsKh4gGgbP0sd/s320/DougSmith_wicked.jpg

“Four Companions” Image. http://www.flickr.com/photos/autumnmarie/4080095454/

Maguire, Gregory. Wicked: The Life and Times of the Wicked Witch of the West. New York: ReganBooks, 1995.

19 May 2011

Wicked and The Scarlet Letter

The huge issue pot: Maguire's main point?

Gregory Maguires tells the story of Frank Baum’s Oz series through the lens of the modern world. At first I do not understand what he’s trying to say in his huge issue soup. However, after investigation and comments from my fellow classmates, I have discovered he’s building an alternate world of Oz land through current issues.

Maguire’s book address social and political issues that are currently happening just as Frank Baum’s view on populism in the early 20th century. He uses the main character Elphaba to capture and address the current issues. When Elphaba is born, she is perceived as bad due to her family’s sin. Both her parents are highly religious, but she considers herself an atheist. Elphaba’s viewpoint is characterized as sinful and her birth’s foreboding the upcoming series events that would be potentially harmful for her. The clock is also another device in the story that symbolizes the danger of religion.

Despite the topic of religion, the novel also addresses the issue of racism and animal rights. The method of characterization is used again to deliver the themes. For example, Dr. Dillamond, a goat, is considered inferior than other species. He could not be accepted by others like his colleague although his research is outstanding and worth mentioning. The head of women’s university, Madame Morrible, is another example of using characterization to present the topic of animal rights. Madame Morrible supports animal oppression and works directly with the wizard. Under the rule of Wizard, the animals are continued to be discriminated.

Maguires touches on varies issues that are widely discussed nowadays. At first, it might seem very disorganized. The truth is, his novel is a real representation of the modern world. Clearly, Maguires is working toward being Baum of the 21st century and has even succeeded to broadway and the movie industry.

Works Cited

Baum, L. Frank. The Wonderful Wizard of Oz. New York: Dover, 1960.

Maguire, Gregory. Wicked. New York: Harper, 1995.

Gregory Maguires tells the story of Frank Baum’s Oz series through the lens of the modern world. At first I do not understand what he’s trying to say in his huge issue soup. However, after investigation and comments from my fellow classmates, I have discovered he’s building an alternate world of Oz land through current issues.

Maguire’s book address social and political issues that are currently happening just as Frank Baum’s view on populism in the early 20th century. He uses the main character Elphaba to capture and address the current issues. When Elphaba is born, she is perceived as bad due to her family’s sin. Both her parents are highly religious, but she considers herself an atheist. Elphaba’s viewpoint is characterized as sinful and her birth’s foreboding the upcoming series events that would be potentially harmful for her. The clock is also another device in the story that symbolizes the danger of religion.

Despite the topic of religion, the novel also addresses the issue of racism and animal rights. The method of characterization is used again to deliver the themes. For example, Dr. Dillamond, a goat, is considered inferior than other species. He could not be accepted by others like his colleague although his research is outstanding and worth mentioning. The head of women’s university, Madame Morrible, is another example of using characterization to present the topic of animal rights. Madame Morrible supports animal oppression and works directly with the wizard. Under the rule of Wizard, the animals are continued to be discriminated.

Maguires touches on varies issues that are widely discussed nowadays. At first, it might seem very disorganized. The truth is, his novel is a real representation of the modern world. Clearly, Maguires is working toward being Baum of the 21st century and has even succeeded to broadway and the movie industry.

Works Cited

Baum, L. Frank. The Wonderful Wizard of Oz. New York: Dover, 1960.

Maguire, Gregory. Wicked. New York: Harper, 1995.